Keren Landman and Rani Molla

And health care systems are getting absolutely crushed … again.

This flu season’s ferocious start has given way to record-shattering levels of transmission — and massive strains on the American health system.

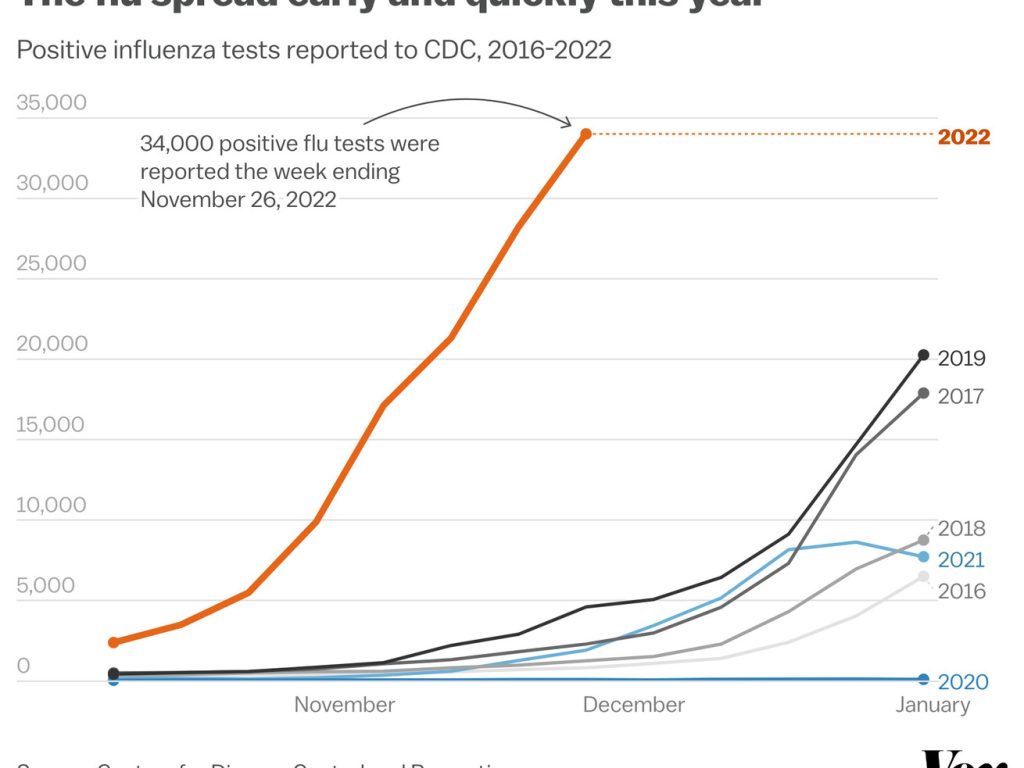

In the week ending November 26, more than 34,000 positive flu tests were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from labs around the US, as shown in the orange line on the chart below. That’s more positive flu tests than have been reported in any single week during any flu season on record, going back as far as 1997.

The trajectory dwarfs the past six flu seasons, including the relatively bad 2019-2020 one that immediately preceded the start of the Covid-19 pandemic (shown in the black line).

Keren Landman and Rani Molla

Some portion of this steep rise in cases is related to the fact that more people are being tested for the flu than in previous years. Over the month of November, about twice as many flu tests were done at clinical labs nationwide as during the same period last year (about 540,000 versus 265,000). More testing means more cases will get picked up.

However, there are corroborating warning signs that this is truly a bad season. Flu hospitalizations have been off the charts and are rising quickly. In a press conference Monday, CDC director Rochelle Walensky said there have already been 78,000 flu hospitalizations this season, or nearly 17 out of every 100,000 Americans. That’s “the highest we’ve seen at this time of year in a decade,” she said. In keeping with past trends, the highest hospitalization rates are among adults 65 and older.

Keren Landman and Rani Molla

What’s making these high hospitalization rates particularly concerning is their overlap with surges in other viruses causing many people to get sick enough to require admission. One of those is RSV, which has been packing pediatric hospitals for more than six weeks. And while Walensky noted there were signals RSV transmission was slowing in parts of the country, Covid-19 hospitalizations recently began to tick upward.

An important reason for the convergence of these viral waves: low population-wide levels of antibodies against many common colds and the flu. Pandemic-era preventive measures delayed first-time infections among many children — which, while good for individual children’s health, meant a higher number than usual were susceptible to severe infection when those preventive measures were lifted. (More on the concept of “immunity debt” and how it can be dangerously misinterpreted here.)

We can still flatten the flu season curve

Americans are also not doing everything they can to protect themselves from respiratory viruses: only a quarter of adults and 40 percent of children have received a flu shot this season, and 15 percent of adults eligible for an updated Covid-19 booster dose have received one.

That represents important lost opportunities for prevention: This year’s flu shot is expected to be a particularly effective one, noted Walensky, as it is a good match to the circulating strains of the flu, which vary year to year. However, it only works if people get it.

Additionally, many of the preventive measures proven effective during the Covid-19 pandemic are going broadly unused, even though they would also be helpful in preventing the spread of other respiratory illnesses. There has been no great push to implement a high standard of ventilation and filtration inside US buildings. Only one-quarter of Americans have changed their behavior to reduce viral exposure. And a minority of Americans frequently wear masks outside their homes.

Amid the flu surge, medication shortages are complicating efforts to prevent severe disease and treat bacterial infections that can follow in the wake of some flu infections. Additionally, staffing shortages that intensified as a consequence of the pandemic have put pediatric hospitals in the position of caring for a massive wave of sick children with even fewer resources than they had before. Although pediatric health care organizations called for a national emergency declaration to support their response to this surge, none has been forthcoming.

In the US, flu infections normally peak between December and February. It remains to be seen whether the current early flu surge will translate to an early flu peak — or instead foretells a protracted period of extraordinarily high viral transmission, with increasingly crushing burdens on health care workers as more people get severely ill.

After a punishing few years, it’s not clear how much more strain the American health care system can absorb.